This is still a draft and needs to be edited one more time before it goes to our publisher!!! This will be in final form by June 1

NO SUCH THING AS A BAD KID:

THE NEUROSCIENCE OF RAISING AND TEACHING CHILDREN

CHAPTER 1

THE FUTURE OF A CHILD’S BRAIN

Neuroscience will have a greater impact on humanity and especially children than information technology (IT), artificial intelligence (AI), the wheel, and fire have all had combined. That is why my book, No Such Thing as a Bad Kid: The Neuroscience of Raising and Teaching Children was written.

I am also worried.

Ultimately, the explanation for this startling statement is simple.

IT, AI, the wheel and fire can and have been used for the benefit of children as easily as towards their detriment. Today, information technology and artificial intelligence are now having profound benefits, but they have also demonstrated serious misuse and concerns.1 Neuroscience tells us why this is true, but more importantly, how neuroscience can be used to bring out the best in everyone, especially children, by what we came to call brain-based methods that are understandable to everyone and surprising to just as many.

The future of a child’s brain is that our current and advancing knowledge of the brain will enable us to mold shape a child’s brain to accept the behavioral standards and values of any society, culture, or political persuasion it is exposed to. The brain doesn’t care. It does not discriminate, starting even before the first day of birth. As children grow and are surrounded by the world they are raised in, love and understanding can become as acceptable as hate and prejudice. Terrorism can become as acceptable as pacifism.

Our knowledge and scientific understanding of the human brain has been due to our ability to use new technologies to begin untangling the labyrinth of over eighty billion brain cells, called neurons, and the, once thought, incomprehensible number of interconnections they have with each other.2

These technologies include positron emission tomography (PET), near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), magnetoencephalogram (MEG), electroencephalography (EEG), and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). among many others.3 In addition, the ability to engineer the molecular biology of hormones and psychopharmaceutical drugs adds to our understanding and ability to change a child’s behavior and influence a child’s emerging beliefs. That still is only the beginning. The ability to alter the genetic profile of a child has begun to lift its head in the twenty-first century.4 We have begun to identify the genetic basis of many behaviors, both aberrant and simply preferred.5 This will cover the spectrum from autism spectrum disorders to the temperaments of a child and varieties of geniuses.

Since these technologies have the capacity to impact a child’s development, we are left with an uncompromising question. For whom and in what ways will we choose to use this knowledge to change a child’s behavior and beliefs? That question leads directly to legal, cultural, ethical, and religious considerations, not just psychological and psychiatric recommendations.

In my book, I use the word “child” to describe anyone who is under twelve years of age and adolescence as a child who is between twelve and seventeen years of age. This distinction is important because the brain of a child changes dramatically after birth up to the age of about six and then again at the beginning of adolescence until the late teens, especially in the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in cognitive processes such as thinking, solving problems, and planning

My book, however, is neither a lecture nor a presentation of the intricacies of the human brain. Rather, it is an invitation, an explanation of the neuroscience immersed within the lives of thousands of children as told through their stories and their time with us in multiple educational and therapeutic environments and especially in our residential program. This science brings us to a new frame of reference that offers new methods to raise, educate, and help children in need. Some of these methods may sound familiar, but others may seem unusual, perhaps surprising, and even controversial. Taken as a whole, their application gives rise to significant differences with current theories of child development and many of the behavioral and therapeutic methods that grew from them. That is because our evidence is based upon the dynamics of how the brain works. Using neuroscience for the better is the intention of this book, and also why it was written.

Our efforts to incorporate neuroscience into how we raise and educate children started in 1981 with the opening of Mohonk House. We began as a very large twenty-two room residential home for children who had been abused, neglected, simply thrown out of their homes, or who ran away in the very wealthy town of Westport, Connecticut. Almost all were between the ages of eleven and seventeen. Before long, numerous programs were introduced to children in underprivileged cities and in schools, treatment facilities, and families in the United States and then overseas. This included children with traumatic backgrounds but expanded to include children from typical familial and educational lives who had no predisposing clinical issues. This also included children with learning disabilities as well as young geniuses.

My book is not an academic compendium for neuroscientists. It is for parents, teachers and child-care professionals involved in caring for and loving children as they begin their journeys in life. However, in addition, I hope many neuroscientists will be moved by the life stories of the children whose lives changed by incorporating the neuroscience they know so well.

The hope is that this book engenders both an understanding and appreciation of the immense impact our knowledge of the human brain has now begun to have and will increasingly have on the lives of children while touching the heartstrings of the reader.

A PERSONAL NOTE

For me, my concern and motivation about the extent humans can be influenced and transformed by what their brains are exposed to emerged in my own brain over years starting as a child. I saw photographs and descriptions of the torture and horror that the Nazis committed on women and children, the elderly, the sick, Jews and gentiles as well as anyone whose ideas and behavior they did not like, essentially humanity in general. How could an intelligent and civilized people do such things? I was told they were brainwashed. The word brain became implanted in my own brain. I was so moved by what I saw and read that before long I could not look at any more photos or even listen to any more stories my father told me about his experiences in WWII. He was a spy. On the heels of those very disturbing impressions, I read Brave New World and 1984. Why could those horrors not also be possible? On the other hand, I was pacified believing the opposite could be equally possible. Words such as peace and cooperation could also resound as a mainstay as a new century approached, especially in the minds of children. Essentially, what this means is that the brain, any human, can learn to adopt whatever values, beliefs, and acceptable behaviors it has learned and been exposed to.

My motivation and concern resulted in studying at MIT, engaging in neuroscientific research, and obtaining my doctorate at Boston University with the involvement of my colleagues at MIT and the introduction of neuroscience into the fields of child development and education. My career then entered the clinical field, and I was employed, continued research, and taught at numerous psychiatric hospitals, schools, and universities. After Mohonk opened, I was invited back to MIT as a visiting scholar because of my penchant to emphasize the importance of clinical applications of the rapid advancement we were making in the field of neuroscience.

IS NEUROSCIENCE CREDIBLE?

Yes. Neuroscience carries more weight because it is grounded in the so-called hard sciences such as physiology, anatomy, and biochemistry, which are primarily based upon quantitative and objective scientific research. On the other hand, child-caring professionals, teachers, and parents have relied upon the research and recommendations of what are called the softer sciences of child psychology, and social, educational, and behavioral research. Such research has advanced us remarkably but has also been much more dependent upon qualitative and subjective interpretations of their research resulting in a diverse accumulation of theories and methods. The result is that often new ideas and theories are given an opportunity to shine as new stars but then are often replaced by even newer theories on bookshelves before a spattering of years have passed for most.6 This extends from the most authoritative and structured theories of child development to the most permissive and child-centered theories.7 We are once again left with a question. Which is better and for whom? Neuroscience opens the door and finds answers to those questions.

Mohonk took the first whole-hearted effort to align the brain with a child’s life. Still, the momentum to begin to apply neuroscience to the human condition has essentially only just begun and is coming to the fore.

More than two hundred universities now offer degree programs related to neuroscience. In 2002 the Harvard Graduate School of Education began a degree program called Mind, Brain and Education. The American Psychiatric Association recognized neuropsychiatry as its own diagnostic and clinical field. MIT changed the name of the Department of Psychology to the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences to begin the interface with neuroscience and clinical applications.

The public seems to be increasingly tuned in as well. The number of books related to the brain and neuroscience has increased over twenty-fold since the 1990s, which President George H. W. Bush declared to be the Decade of the Brain. The number of articles in journals, magazines, and newspapers that are related to neuroscience has increased almost thirty-fold in the same amount of time. Presently, there are at least 100 annual conferences that relate to understanding how our brains work. Many have addressed the impact that neuroscience can have on society. For example, in 1999 the Learning and the Brain initiative was formed to connect educators to neuroscientists and researchers. They focused on discovering the impact of different teaching strategies on the brains of children. Another annual conference has stretched the relevance of neuroscience even further. The NeuroLeadership Institute started in 2008. The conference teaches leaders in businesses, education, and government how to incorporate the value of neuroscience into their respective fields. The implication is that what we know about how the brain works can help guide society in our twenty-first century. This was preceded by the formation of the International Neuroethics Society in 2006. Leaders in the field were beginning to realize that their research covered a much larger domain. Ethics was an inherent attachment to what our research meant for our future.

The goal to unravel the finest details of the human brain is in sight. That sight seemed more like science fiction than a possibility less than twenty years ago. In 2009 the National Institute of Health launched the Human Connectome Project whose objective is to establish a complete detailed anatomical and functional connectivity of the human brain, and in 2013 President Obama supported the BRAIN Initiative with an initial $100,000,000 research effort to map the human brain in all its detail using new technologies. In his 2013 State of the Union Address, President Obama said that “our scientists are mapping the human brain to unlock the answers to Alzheimer’s,” and added, “Now is the time to reach a level of research and development not seen since the height of the Space Race.” The time has come. However, the United States may not have the leading edge in discovering what makes us tick. We may be significantly further behind other countries in this endeavor. The European Union, for example, already has a similar initiative up and running called The Human Brain Project, funded with over $1,250,000,000. China may be farther along than Europe or the United States with older initiatives such as Brainnetome, whose goal is to completely map the human brain including its functional connectivity to behavioral research. Their first annual meeting was held in Beijing in 2012.

Humanity is taking neuroscience seriously, and this merging preoccupation has accelerated by advances in at least four dramatic areas of research which have awakened concern about how neuroscience will be used in society, especially in shaping the life of a child.

NEUROSCIENCE IN THE LIFE OF A CHILD TODAY AND AROUND THE CORNER

The advancement in neuroscience impacting a child’s life today and which will direct a child’s life around the corner, probably within twenty-five years, is due to at least four discoveries. The first is the dramatic discoveries related to the relative influence genetics and the environment a child is exposed to has as her life unfolds.

Genetics or the Environment?

Our brains are malleable. Neurons change based on both genetic blueprints and the effects environmental stimulation has on the brain. Today we have begun to have the ability to observe and quantify the changes each has. Such knowledge transports psychological and educational theory into neurophysiological terms. This malleability is now popularly called neuroplasticity and is the first of four discoveries that will change our future.8 The result is the environment takes advantage of this blueprint and together they create who we are. These changes are especially evident, beginning prenatally, continuing the moment a child is born and up to about six years of age and then again with a resurgence among adolescents between eleven and eighteen or nineteen years of age.

The neuroplasticity of our brains provides the basis for different abilities and temperaments that children have been born with and develop as a child grows. We know that now. It is not a far step to question, consider, and realize that a child’s genetic blueprint and the environment a child is exposed to contributes to different types of learning abilities, behavioral abilities and disabilities, as well as psychiatric disorders. Today genetic markers for Aspergers Spectrum Disorders, Schizophrenia and a growing list of human behaviors have been uncovered.9

There have been historic differences among theories and methods based upon the influence of genetics as compared to the environment on brain development and human behavior. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, genetics was generally preordained as the primary basis for determining who we become.10 In the twentieth century the influence of the environment became predominant. Any child, it was said, is primarily a blank slate and could be conditioned to become whatever we want.11 Genetics took a beating, but now we know better. Our genetic foundation and the environment are both central to what makes us who we are. We have uncovered the genetic and environmental impact each has on the human brain down to the individual and molecular level of neurons.

This has now been extended much further, and we have discovered a new surprising and unforeseen twist.

Many of our genes cooperate with the influence of experiences on our brain and our experiences cooperate with our genes. The impact of our genes can be diminished, enhanced, or altered through the influence of experiences. This has even been given a name, epigenetics.12 This is the second major discovery that is impacting theories of child development. Discoveries in the field of epigenetics give rise to many fascinating discussions and debates regarding child development theory and methods to raise children. How, for instance, might we be able to dimmish or eliminate any genetic characteristic by selective environmental influences. The brain-based methods elucidated in this book bring that to the fore.

To add to that commotion, the latest rage in genetic engineering has been research related to our third major advancement in neuroscience. It is called CRISPR. CRISPR is a technology that has begun to enable us to identify specific genes associated with human maladies and replace them with healthy genes that will be able to eliminate such afflictions. So far, for instance, five genes have been identified that relate to Asperger’s Spectrum Disorder.13

The wide-eyed excitement of neuroscientists involved in such research cannot stop there. They, and now all of us, are pressed to think of where such research using CRISPR could take us legally, politically, and ethically as we have begun to unlock the genetic door of different types of intelligence, abilities, and temperaments. That being said, we are left with a momentous question that has begun to reach out to our conscience. How much and in what way would we use such knowledge to shape the environmental experiences in raising children and altering the genetic makeup so every child could be what we want them to be?

Genetics, environmental influences, epigenetics, neuroplasticity, and now CRISPR can be interwoven to create who we are. How do we want to weave the life of children? What abilities do we want to enhance? What temperaments do we want to diminish or even eradicate, if any at all, and on what basis? How do we wish to preserve or augment freedom and independence of thought however we choose to define those aspirations? The fact is, such concerns cannot be dismissed in novels or science fiction any longer. They are knocking on our door, some have come in, and locking the doors won’t work.

All these ingredients for changing the brain of a child have a common core and a common thesis. Regardless of their cumulative efficacy, the accumulation of all of them still suggests that there may be very little or no limit to the extent to which a child can be shaped and influenced by whatever experiences, doctrines, dictates or values he is exposed to. Could a Nazi have become a saint, a saint an evil war monger? Such concerns reflect the real day-to-day world we will come to live in and certainly one of our children and our grandchildren will inherit. That horizon also raises concern, probably unease and almost certainly confusion. Is that horizon one where humanity could fall off the edge or discover inspiring terra firm and wonderful possibilities?

Neuroscience can show us how to get to our better angels.

Neuroscience brings us to new methods which advance us much closer to what we thoughtfully choose is better and for whom. That is because neuroscience and brain-based methods, brought to life among the stories and lives of children within the chapters of this book, require evidence that is backed by hard science first and foremost

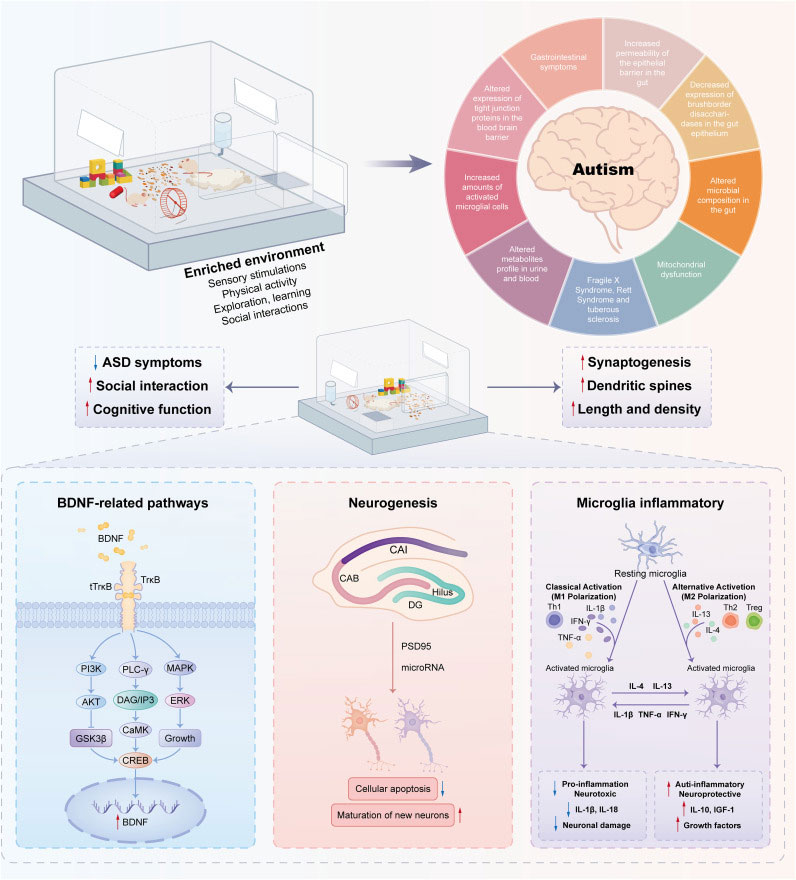

Molecular insights into enriched environments and behavioral improvements in autism: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Molecular insights into enriched environments and behavioral improvements in autism: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Figure 1

The accumulation of what truly has become an overwhelming aggregate of information has resulted in a conundrum. We can now collect more data than we can easily analyze. But now we can. It is called Big Data analysis and is the fourth major advancement that has accelerated our knowledge of how our brains work.14

Big Data analysis enables us to evaluate and make sense of quintillions (1018) of bytes of information. That number is more than one billion times greater than was possible twenty years ago. It is the equivalent of a teacher taking into account the individual learning styles, abilities, temperaments and day-to-day changes in all of her seventy to hundred and ten students. Essentially, to put an exclamation on such a number, that means we will have the potential to evaluate the effect that most, perhaps all, genes have on every neuron related to every memory, sensory input, and response of an individual’s life. This will enable us to specify the genetic and environmental influences that shape who we are. Today we have begun to evaluate adults and children with schizophrenia, attention deficit disorders, autism spectrum disorders, and more based upon Big Data analysis. With such an ability to specify the impact genetics and specific environmental experiences have on a human being, we are many steps closer for society being able to specify how we want an individual to think and behave. This is not science fiction. It is possible, and a door has been opened to untangle the labyrinth. Neurophysiological research can distinguish anger, love, motivation, empathy, brain-based differences from car mechanics to neuroscientists, the effects of memories on behavior and any other behavior we wish to describe. We are now reaching a horizon we once thought could never be touched, but now we have a firm hold on the map with Big Data’s guidance to ask us where we want to go and how we can achieve the goals we decide are important in a child’s life

Today, however, these guiding lights in research have still lit different paths. Even as some psychologists and educators have begun to experiment with brain-based methods, they are more of an afterthought or just an “add-on” rather than a perspective that digs into the methods they use and the way they personally interact with their charges every day. That does not carry the day. For parents, teachers, and child-caring professionals applied neuroscience is still as meaningful and reachable as a distant star and usually little more than an abstract head nod on its relevance to child development as it is practiced. On the other hand, neuroscientists have been largely focused on unadulterated science. Brain-based behavioral research has historically been limited to assessing the brains of small rodents running mazes and Rhesus monkeys deciding which colored box held a raisin. Today, however, neuroscience has begun to find its place and has expanded to study and assess the brain in a living, breathing human, including children of any age. Using these technologies, we can evaluate the neural networks associated with the emotional or behavioral state of any human simply by showing the subject photographs, speaking words or even asking a subject to think of something that makes them cringe, smile, get angry, or feel at peace.15

An added dimension to this labyrinth is the sudden accelerating field of what is called brain–computer interfaces (BCI). Prosthetics are used to enable a human to move an artificial limb. A human can think of moving his leg, and the steel and titanium leg can move how he wants it to. Now artificial intelligence has been used to read a human’s thoughts via the output of an individual’s brain waves to move a computer cursor on a monitor while the individual remains motionless.16 In addition, it has been shown that a small silicon-based chip attached to the skull of an individual can be used to interface with the internet. The chip can stimulate neurons and provide answers to most any problem or discover any fact.17 The information is then spoken or written by the individual. Perfect scores on certification tests or SATs are in the cards. That raises questions, doesn’t it? Where will this go? How will it be used? The potential for good is as easy as the potential for misuse. Regardless of how quickly the future is reconstructing our world with the introduction of internet technology, artificial intelligence and BCI, the brain-based methods offered in this book leave an open door for every human and his independent brain to make choices. The brain-based methods described in this book show how technology can be served for our better good rather than misuse.

How practical and scientifically relevant is neuroscience today? Just as important is how this research can be increasingly adapted to the life of a child today and around the corner?

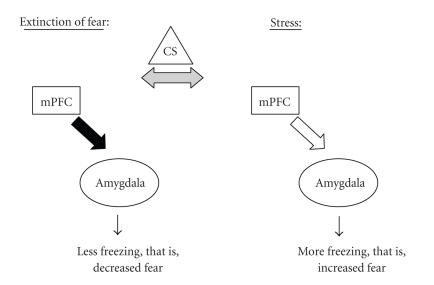

At Mohonk, we did not do brain scans of the children although on several occasions we asked our gathering with a bit of whim if they would be interested in doing that. It was fascinating. Almost all children wanted to do it including those who had a diagnosis of an attention deficit disorder or learning disabilities. Children who had been identified as having an intellectual disadvantage or who believed they were “not too bright,” tended to be resistant. Nevertheless, our brain-based methods were created based upon understanding and taking into account which areas of the brain were activated when a behavior we wished to influence, improve, or change occurred. For example, anger and rage stood out. There is a tipping point when physical restraint might be necessary. A region of the brain that includes an area called the amygdala takes hold. (Figure 2) At the tipping point words have little or no influence, even with threats. However, before that tipping point is reached, the child’s so-called executive thinking regions of the brain still can overtake and suppress emerging rage and gain a foot hold.(Figure 3). We used that to our advantage in highly unusual ways.

The role of the medial prefrontal cortex-amygdala circuit in stress effects on the extinction of fear.

The role of the medial prefrontal cortex-amygdala circuit in stress effects on the extinction of fear.

Figure 2

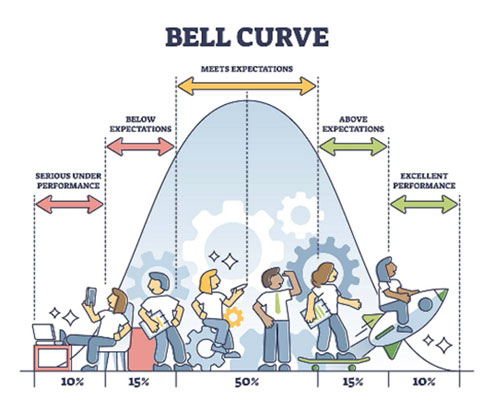

There is an additional concern that separates neuroscience from the softer sciences. Virtually all methods that have grown out of behavior-based psychological and educational research conclude with persistent neglect. It is represented by a classical type of distribution curve as shown in Figure 4. It is called the normal curve. A normal curve is a perfect distribution. That is, there are as many individuals equally distant from the average who are below the average as there are above the average. Distribution curves show that most children settle into the average range whether it is any type of intelligence we wish to delineate or any behavior that piques our interest. The same holds true for a child’s height and weight, effectiveness of medications, etc. The more a child deviates from the average, the less he or she may fit in with established standards, criteria, or expectations. A typical middle-school classroom may last forty-five minutes. That is because it is commonly accepted that the average student will be most attentive and learn more within a set number of minutes. The fact is some children’s prime attention is shorter, and they will learn less. Others may fall apart and disruptive behavior leaps into the arena. Many other children benefit from having more time to go over what is being said or to write more notes, and some get bored because they know the material so well. They would get an A with their eyes closed. Within families, some parents discover they have success with strictly enforced rules. Their children are well-behaved, keep their rooms clean, teeth brushed, and do not eat with their fingers. Other families are successful with much more permissive and child-centered approaches despite pajamas on the bedroom floor and greasy fingers.

Figure 3

Most teaching methods, methods to raise children, or therapeutic interventions are usually effective for a significant number of children, but also extremely helpful to others and even harmful to some. That is based upon how much any child deviates from the average of any method that is applied. Montessori methods, permissive “free-range” methods and strict disciplinary methods such as in military schools and Tiger Mom theories of educating and raising children follow that same rubric.18 Each has their range of successes and failures that reflect the unique collection of gifts or limitations, temperamental predispositions or genetic predispositions of a given child. These methods are essentially orientated to trying to do the greatest good for the greatest number. Fair enough, but neuroscience points on us to much greater possibilities. It allows us to establish a unique prescription to raise and educate every child as a unique child? In that way, No Child Left Behind is not limited to a pleasant-sounding aspiration.

At Mohonk, we incorporated this concept by emphasizing the need to use our brain-based methods in a consistent and dynamic way all the time and by everyone.

BRAIN-BASED METHODS

The brain-based methods we incorporated at Mohonk are based upon the physiology and anatomy of the human brain. Eight have been identified that have a far-reaching impact on raising and educating children. Each is described individually and through what we call practical applications within the chapters of this book. Our methods are embraced by touching, gripping, even very humorous, sometimes gut-wrenching stories of the lives of children who were under our care and in our programs. The sum effect of our methods and these stories, we hope, is inspirational, and at the end of chapters 3-14, we offer suggestions and examples of how the reader can also adapt the practical applications of brain-based methods in many ways with the children in their own lives.

The important point to make here is that our brain-based methods take into account and incorporate many fundamental functions of the brain into raising and educating children. Some of the brain-based methods will have a familiar ring, at least in part, to the methods the reader has read about or uses. However, others are unique, and when taken as a whole, these brain-based methods have shown unexpected and everlasting possibilities for children. We have seen this based upon our use of brain-based methods as painted among the stories and lives of children who we had the opportunity to help in our forty-three-year history. This is possibly the first time such a comprehensive brain-based approach has been put into practice and has been our undeviating objective. By doing this, children have benefited strikingly.

With regard to the efficacy and value of brain-based methods, one only has to realize that virtually every theory in child development, therapeutic methods, and education essentially reflect a presumed and usually unstated assumption that they have a basis in how the human brain functions. However, not enough has been known to be able to support their theories and methods by reference to brain-based research and many are insufficient or even detrimental to many children. This includes everything from behavioral management techniques, cognitive behavior theories, psychoanalytical approaches or even Montessori methods.19 Sigmund Freud and Maria Montessori would whole-heartedly agree.20 They said so. B. F. Skinner would have concurred except that he believed that behavioral management did not need to include reference or even understanding of neurophysiology although he said, it would be an advantage if we knew more.21

We now know more.

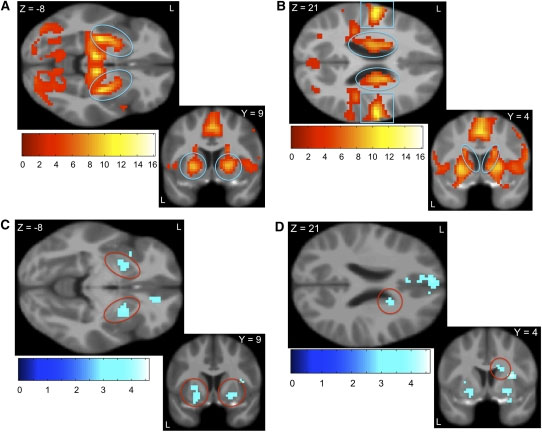

Brain-based methods reflect groups of neurons that form what we call neural networks that serve specific behaviors, sometimes a number of specific behaviors. To date, modern neuroimaging studies, such as functional MRI (fMRI) analyzed with the help of what is called Big Data analyses have defined seven networks of the brain that seem to delineate seven different types of behavior.22 Still, exactly how many neural networks there are and what defines a neural network remains an ongoing research process. In effect, the nomenclature is a bit of a grab-bag, except for one conclusion that overrides any parcellation that any researcher can make. That is to say, behavior and all of its neural networks no matter how physiologically defined are virtually all connected to one another directly or indirectly. They create our thoughts, memories, feelings, actions, habits, wishes and desires that every human has. This includes inhibiting behaviors that get in the way such as a child’s effort to control his emotions or an adolescent’s wish to suppress unpleasant memories.

A few examples will bring this to light. The neural network associated with emotions (principally the Limbic System23) cannot be dismissed as having no effect on areas associated with neural networks that are involved with executive functions such as reasoning, decision-making, and planning; principally the Prefrontal Cortex.24

When solving a mathematical problem, a child may not show any facial sign or express any emotion at all, but, in fact, may feel overwhelmed, happily challenged or simply motivated. A child who shows no emotional expression still has a repressed emotional reaction in the same way a child may suppress emotions when told to behave or suffer the consequences. In neurophysiological terms, the repression of emotions that are not actually observed is called inhibition, and this reflects the impact neurons that inhibit emotional reactions have on the Limbic System. The point to be emphasized here is that emotions affect our behavior and can never be dismissed as irrelevant when developing methods and practices to raise or educate children.

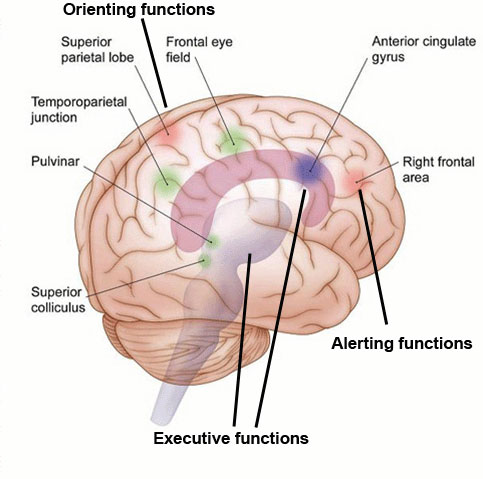

Another simple everyday example expands on this. When a child turns his head at the sight of his mother returning home, his visual cortex ignites along with his motor cortex that enables him to turn his head to see her. When she calls Jamie for help with the groceries, his auditory cortex comes into play and emotions as well. He misses her and is especially excited by the ice cream that she said she would bring with her. Figure 4 shows the excited anticipation ice cream can have on the brain of a child when his mother comes up the driveway. Certainly, his attention is focused. Paying attention involves a number of areas of the human brain including the frontal, parietal, and temporal areas of the cortex as well as an area called the thalamus among others.25 The pre-frontal cortex is also playing its part as this child decides that waiting more than thirty seconds is too long, and he runs out the door to grab the groceries.

What does all this have to do with the classroom and talking to your child about behaving himself? A child’s attention and interest in what is being said is directly affected by his abilities, temperament, habits, memories, worries, fears, and more. How is a child’s receptiveness influenced by such ingredients? The teacher’s or parent’s ability to integrate the individuality of each child seems daunting, but everyone tries their best of course. The outcomes vary across the board from abject failure for some children and stunning success for others. Brain-based methods seem to shine a light and create a bridge on how most every child can achieve stunning success.

Frequent ice cream consumption is associated with reduced striatal response to receipt of an ice cream-based milkshake.

Frequent ice cream consumption is associated with reduced striatal response to receipt of an ice cream-based milkshake.

Figure 4

HOW THE BRAIN LEARNS BEST

Within that framework, our first brain-based method was born. It is called How the Brain Learns Best

Scans of the human brain have brought forth new ways to incorporate learning methods for children. Today behavioral conditioning is sacrosanct in education and, in fact, is at the heart of most if not all theories of learning and therapeutic methods as well as the way we raise our children. Many might disagree. However, from the perspective of the human brain it bears out. Classical behavioral conditioning, operant conditioning, observational learning, cognitive learning theories, constructivist learning theories, experiential learning theories, and social learning theories as well as cognitive-behavioral and Gestalt therapeutic theories and theories of mindfulness have a common denominator in the brain. Whether the input is from the outside world, stimulation from one’s own body, memories, mindfulness and self-reflection, or genetic input, neurons respond in the same way: cause and effect. When we say “actions speak louder than words” or “a picture is worth a thousand words” we are in effect saying, that both approaches influence our life experiences from the same basic neural process, just different and overlapping areas and neural networks of the human brain. They are all experiences a human has, and the human responds. When a child forgets to tie his sneakers, he learns quickly that he must tie his sneakers. The resulting learned behavior is simple behavioral conditioning, cause and effect. At another extreme, meditation is the same. When we meditate, we learn to pacify the brain, the environment that works best, the position of the body that works best, the reinforcement that it provides. The neural networks that are involved during meditation can be scanned. The Dali Lama enjoyed the process of. having his brain scanned while meditating. His word after the experience: “Wonderful.” Meditation was wonderful, scanning his brain was wonderful. It was all reinforcing. His brain said so. Every behavior we make, every thought that crosses our mind effects our brain.

How does that take us to How the Brain Learns Best? The answer is that there is another way of learning in the fields of parenting, educating, and helping those in need that encompasses and differentiates most if not all methods and theories that have been promoted in the past.

We can make a distinction between two different ways of learning that point us to practical applications for children.

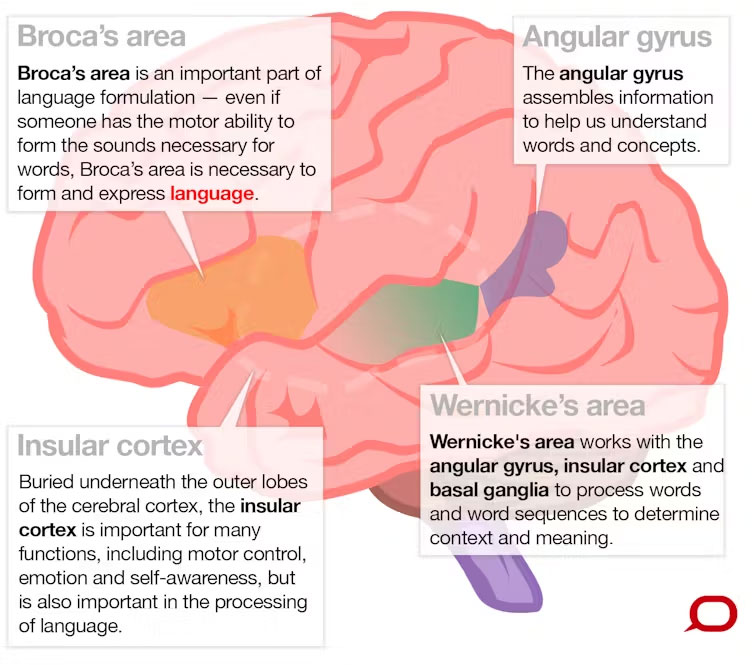

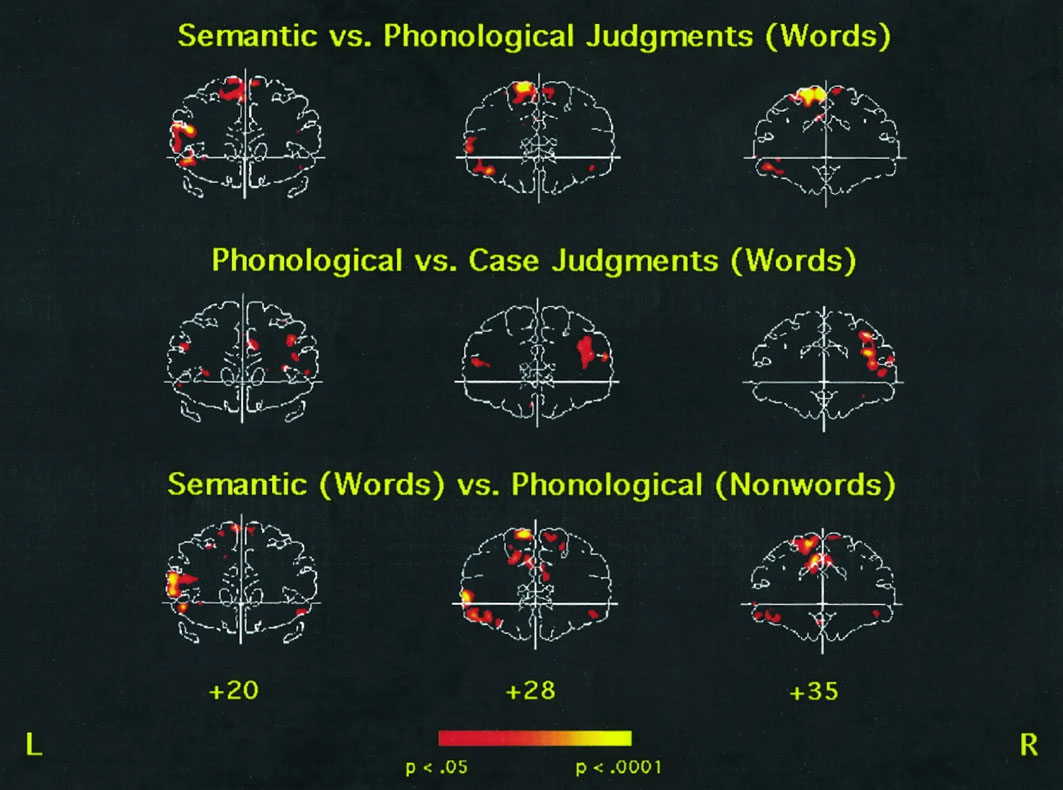

The first type of learning we distinguished was through language as reflected by using words, mathematics, and symbols such as in musical notation. They reflect distinct and well-known areas of the human brain as seen in Figure 5.26 Let us call it symbolic learning.

Without these areas we cannot understand and make use of language, mathematics, musical notation, etc. However, learning by stimulating our senses that does not involve symbolic learning involves distinctly different and well-known areas of the human brain. We become inspired by the sight of an early rising sun over a distant mountain range. Words do not come into play at first sight. Such an experience meant we learned something that was reinforcing and that we will never forget. We listen to the sound of music that we love. There might be words that are sung but imagine simply reading those same words without the music. The inspiration, the stir, the impact is different. Why?

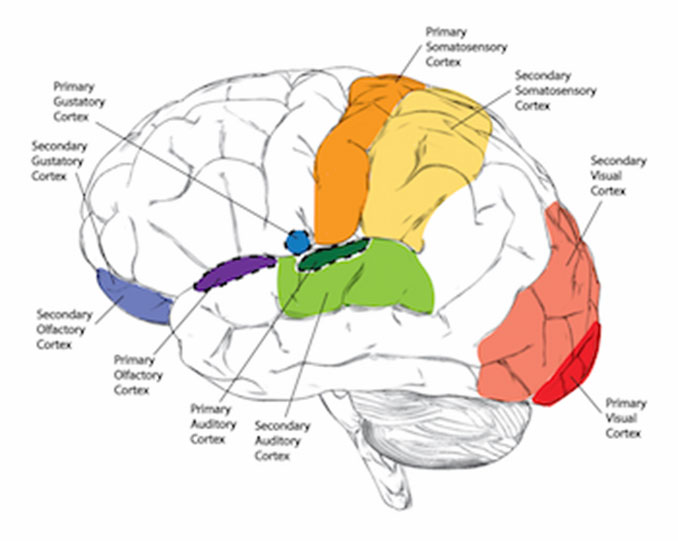

Each of our senses are represented by separate areas and neural circuits and includes sight, sound, touch, smell, taste, proprioception (awareness of body position in space), and balance (Figure 6).27 Words play a different part when we describe our experiences to a friend or write a poem, or author a scientific description of what areas of the brain we are involved in what we experienced. Still, the sensory experience itself is in a different dimension. Let us call this type of learning sensory learning

Brain regions showing most sensory areas of the human brain within the cerebral cortex .

Brain regions showing most sensory areas of the human brain within the cerebral cortex .

Figure 6

In society, language learning increasingly plays a predominant role in shaping the behavior of children as they develop and experience their world. That includes such experiences as listening or reading about what is right or wrong, rules, laws, instructions, history, the meaning and usefulness of mathematical symbols, or instructions on how to bake brownies. That is how children discover what is right or wrong, good or bad, acceptable or not acceptable in their home and in society in general. They also learn that language is the sine qua non for what is considered valid or legal evidence. Sensory learning is just as it reads and is based upon sensory experiences such as watching the way an artist paints, the way a parent’s face expresses her concern and calms an irate sibling. The tone of her voice and body language can both communicate as much or more than the words spoken. A young child learns without words as he constructs a Winnie the Pooh Lego character or as he stares with interest and intensity as a colony of ants scurry around his left-over blueberry muffin that fell to the floor around his chair. Language learning does not have to come into play as the dominant source of information.

Both language and sensory learning are essential and an integral part of a child’s growing mind, or brain if you will. In life, both types of learning occur together to different degrees. However, in education and raising a child sensory learning, more often than not, has been a second-class citizen, an appropriate, even if a necessary, add-on to reinforce the words. As a child grows, language increasingly becomes the dominant way a child learns to behave with his family, school, and society, and it is much more often viewed as the easiest, most efficient, and clearest means of communication and learning.

Most parents, teachers and professionals know that learning through sensory experience is essential. Montessori methods, undertaking science projects, performing what has been learned through dance, song and painting as well as the requirement of internships in many fields attests to that. Still, something is dramatically lacking.

At Mohonk we incorporated sensory learning in two practical applications. The first was by asking children to take the initiative, observe, and come up with solutions to any problem. Of course, that is dependent on the age of a child. Three-year-olds cannot be asked to consider the pros and cons of running across a busy street at the first sight of Disneyland. The youngest child in our residential programs was eleven and considering choices or solving problems was well within his realm. For us, children needed to take the first step whenever possible. They needed to watch and see what happened from their own initiative or watch and see how others tried to solve problems by what they did. The advantage could extend to learning about how to change a vacuum cleaner bag to how to deal with their own parents after watching staff and other adolescents playing the part of a parent in our role-playing therapy groups.

“Ben,” we asked, “Can you try and figure out how emptying the vacuum cleaner bag works,” The next day was Ben’s turn to use it for a week. Ben watched how Miguel emptied a vacuum cleaner bag. He didn’t ask questions. He wanted to try to do it himself. He just watched. The result was that Ben could coordinate the switches and levers without having dust stream over his face, and he was proud of his own successful efforts. Ben’s efforts also increased his awareness of cookie crumbs and pizza morsels left abandoned on carpets when it was his turn to use the vacuum cleaner. He requested that we should all try to keep such scraps off the floors. Such situations as Ben’s were reflected in many situations at Mohonk, both at the cookie crumb level to observing and considering the body language and emotions of words spoken before solving any type of problem.

In a similar way, taking initiative and solving problems expanded to very personal issues.

By using role-playing, we incorporated both language learning and sensory learning. Telling a child he should control himself when his parents get annoyed is very different than playing the part of a parent and then himself and watching his peers do the same, especially in the safe rooms at Mohonk. Such learning sticks to the bones. The result can be monumental.

Finally, Jimmy came up with solutions that grew from role-playing and then being asked about solutions he thought of. He was surprised by his own good ideas and spoke to his parents about practical plans he had as well as his own personal hopes of being able to be part of his family again. They were surprised, even shocked, and also impressed. When Jimmy was at home, he and his parents had gone to therapy and read how-to books for sixteen months to no avail. The ideas presented were good ones, but they remained abstractions, just words. Saying Jimmy’s brain changed from the act of role-playing reads much too mechanical and staged, but the fact is that was what happened After two overnight try-outs and two weeks, Jimmy was greeted at our front door by his parents. He immediately dropped his duffle bag and what was left of his Oreo cookies, and hugs abounded.

Learning about vacuum cleaners and learning how to help contribute to a stable home are the same from the point of view of the brain. Children learn best from sensory learning balanced together with language learning, and the benefits proved outstanding. Too often, it seems, words alone should be the dominant mainstay. They are not.

The second practical application we used was to give all children the opportunity to be involved in as many diverse sensory experiences as possible. Our imaginations were the only limits we had, and we offered as diverse a collection of experiences as staff and children could come up with. By doing this, their senses were engaged, and they learned much more about themselves, their interests and abilities than verbal information alone could provide.

Richie listened intently and watched carefully as he was shown how to tie a bowline knot. He practiced it three times to get it right without hesitation and then belayed off a fifty-foot cliff. Perfect. His relief setting his feet on the ground was only surpassed by his pride in doing it. Learning about other knots could be learned the next time. Richie pleaded for the next time.

Ken brought up the idea of flying in a helicopter to Wall Street to meet rich people and see what they were like. Ken was inclined to think of unrestrained ideas. It happened. To the amazement of the adolescents who chose to go, helicopters were not as scary as they had thought. They also learned that some rich well-dressed Wall Street people had not done so well in school, and all they offered they all should keep on their toes to be successful. Of course, several of our aspiring young adults then decided that becoming Wall Street millionaires was now on their table. Three of the eight who went wanted to learn how to fly a helicopter. Philip was 18. He settled for first learning how to fly a single prop Cessna Skyhawk and went for lessons.

Among the stream of children and cascade of programs that were part of Mohonk, Jose was one of the children who reflected the entrepreneurial spirit. He suggested we open a consignment and donation store. Certainly, their senses would be immersed with how their brains learn best. Everyone had seen the endless donations the public offered to us, and we had become infamous for our annual tag sales. Opening a retail store seemed like a stretch to some, but the excited anticipation carried the day. The children would run it as much as possible. Three of them decided to go to Goodwill and several local consignment shops to absorb the experience and get ideas as well as asking questions. Discovering how to get donations and consignments, how to interact with customers, what hours to be open, etc. was valuable but only got them to first base. The experience of organizing donated baseball cards, side tables, toasters, difficult to describe antiques, a plethora of jewelry and a dictionary full of wares got them to second. Dealing with credit cards, cash, and banks got them to third, but getting home required dealing with an enormous variety of people from three-year-olds to octogenarians, generous kind people and thieves, essentially a universe of humans. Reading how-to books and listening to volunteer consignment experts provided meaningful input, but the personal excitement, adventure, confusion, and the overall sum of sensory experiences was irreplaceable knowledge and brought everyone to home plate. Much more than selling donations was learned.

Among some of the most touching experiences described within the chapters of my book, was traveling to a host of countries so our flock could meet children from different cultures, religions, and backgrounds. Most children carried preconceived ideas about the children they would meet, and biases were not uncommon. However, meeting these children in person and having the opportunity to discover children anywhere, whether rich or impoverished, Muslim, Christian, Jewish or any other religion, any color or background have much more in common with them than their differences. That was our hope.

This was not difficult to accomplish. Such shared experiences as ice cream and basketball balls brought comradery, smiles, and high fives as their mutual reward. Differences they may have had, including biases and beliefs, carried little weight when they played together with players intermixed from different countries or when the collection toasted each other after being offered seconds on chocolate-chip ice cream. Such an experience was ripe with sensory information, and, as a result, much sensory learning occurred without the need to depend upon only symbolic learning, that is, in this case, spoken or written language about the countries we were visiting and telling children they should respect the children they would meet.

The sum of our experiences was that when we incorporate language and sensory learning together as an integral necessity as much as possible, learning is enhanced remarkably and deeply. That is how the brain learns best, and that is how our first brain-based method got its name. How the Brain Learns Best.

HOW THE BRAIN THINKS

The learning experiences brought to bear by How the Brain Learns Best tip-toed into a second brain-based method. It encompassed thinking and involved very different neural networks of the human brain.

Thinking is not an abstract term or an educational or psychological concept, and it is different than How the Brain Learns Best as described previously. In education and psychology, there have been many different theories of what it means to “think.” From the perspective of the brain, however, they have one common foundation, and it is that they reflect the functions of the frontal lobe, and especially the pre-frontal cortex (Figure 7). That is where the brain processes and makes sense of what it has been first learned through language and sensory based learning. 28

Figure 7

I called this How the Brain Thinks, and we gave life to this second brain-based method by using several practical applications. The first was we asked questions ad infinitum rather than giving direct orders or ideas as often as possible. That was the catalyst to make children think rather than always being dependent upon others to solve problems, rushing to judgment, or blindly accepting what is seen, heard, or read. Socrates would approve.

“Jeremy, should we keep the kitchen open all the time, twenty-four hours per day.” Jeremy said “no,” as ninety-five percent of the other children typically answered.

“Okay,” why not?

A typical response was that others would steal food or not share apple pie.

“Okay, who would do that,” we asked.

Most everyone said they would not. As a result, we set a challenge and put the pedal to the metal. Everyone wanted to see if we could leave the kitchen open and if anyone would steal food or not share. The result was that we never kept the kitchen locked and asked constantly if the plan was working. It was, and, as a stroke of humor, we kept several apple pies in the refrigerators. Chuck was big. He played football and had a thirty-eight-inch waist tied to his six-foot three-inch frame. He asked if he could have a second piece “cut kind of large.” He was given a question. “What do you think you should do to see if it’s okay?” Chuck asked the members of our crowd if it was okay. They were fine, and Chuck was at peace in less than two minutes. The end result was that the kitchen was virtually never locked. Now and then unannounced state inspectors would come by and were always surprised. They didn’t like that rule. They did not believe that adolescents could show such self-control and restraint. Abe gave them the best concise answer when asked. “It’s not a rule. We just do it.”

One of the most interesting results of asking about setting rules and regulations was that virtually every child believed there needed to be many rules. That reflected the way their world worked before coming to Mohonk. However, we challenged every child to think about what rules we needed since they thought rules were necessary. The result was startling. Among the variety decided upon was that they did not want the house to be a mess and divided the jobs up among themselves. They came up with a “lights out” standard because some wanted to get to sleep earlier than others. In effect, they created most rules that they all could live with including the staff, often with our guidance by asking questions about their ideas.

The result was that there were rules, but comparatively few rules compared to any child-caring facility we could find. Still, we would never be considered as being a “permissive” do-as-you-please organization.

If a rule was not followed, it was always pointed out individually, but again, only with a question. “What do you think you could do to prevent that happening again?” They had to think, take responsibility and come up with ideas. What is important to emphasize here is that such questions were not presented as an implied warning at all. Questions were offered as interesting, curious, and even exciting questions. Children could tell just by our enthusiasm, curiosity, and especially our respect towards them. They also knew that punishments and reprimands were something that we really did not like. The staff cringed; I cringed as much as the children. However, that did not mean that we were a permissive and open-ended playground. Everyone was held accountable consistently. That was the second application we used with How the Brain Thinks. Each child quickly learned that they had to think and solve problems, and they were capable of doing that.

Our approach did not sit well with the State license regulators. They were mentally immersed in the need to provide rules and structure and not leave it to children to think and at least begin to take ownership of the decisions they made. We were becoming a bit controversial, but when state inspectors talked to the children, they could not help but be impressed.

“What happens,” they asked, “when you break a rule?” Richard gave the most concise answer. “We don’t really have punishments, because, if I forget, I have to come up with an idea, so it doesn’t happen again. That’s my job.” Still, for the State this was unknown territory and there was understandable skepticism.

Asking questions was almost a mantra. It was a way of life. That was good because it could extend to the far reaches of the mazes and landscapes of their lives. As adults, they would be inclined to think about the different choices they could have and, as a result, choose more thoughtful decisions, new ideas, accept what is offered and required or even rebel in some manner if they thought necessary.

However, we are still left with a perplexing concern. A child becoming an adult could thoughtfully choose mistrust, animosity, aggression, or hate as easily as trust, goodwill, nonaggression or love. That is because of the beliefs and attitudes a child is brought up with by parents and then by the norms of society and culture as well as the media children are exposed to. As such, as a child grows, he then finds acceptance and love by accepting the life he has been surrounded by. He learns what he comes to believe is right or wrong, good or bad, and that extends to the values that surround him and how others are treated. Mistrust, animosity, aggression, or hate can lift its head when there are others who believe in different ideas of what is right or wrong, good or bad or whose values conflict with what has been planted in their minds. A child, his brain, accepts the social environment that is put before him. If so, how could we deal with that? How do we try to bring trust, goodwill, nonaggression and love to enable children to become enlightened purveyors of the future that will be in their hands?

We can, and such an optimistic and idealistic sounding hope can be led by our knowledge of the human brain.

The genetic evidence begins during the first months of a child’s life.29 An infant is drawn to the softness of a mother’s touch and the gentle sounds of her voice. That is trust, goodwill and love, and for babies that is rewarding and reinforcing. An inherent rejection of the mother by a baby with screams of repulsion and dislike is virtually non-existent across cultures, religions, and history. Babies prefer feeling good, and they are rewarded. They scream when they need attention and milk, soft touches and voices.

At Mohonk we started with what felt good and was rewarding for each child, all between the ages of eleven and seventeen with an occasional eighteen-year-old. We did that by not spelling out what was right or wrong, good or bad about any child, or what they believed. Instead, we asked questions. We made children think, and by doing that enticed each child to come up with different ways of solving a problem.

“What good would hating your parents do? Would it change them?” Peter thought for a few seconds and then said no. “Then what can you do to change them?” Peter had to think and, on the questions went, until he discovered without realizing at first that he also had to change. He made a list of possibilities of what he might try. Peter was back home within six weeks.

Sometimes on a larger scale we might talk about subjects that will affect them personally and extend to thinking about the world around them, the one they will inherit. .

“Do you think the Palestinians and Jewish people should hate and kill each other until one side is all dead?” That was a leading question, of course, but it began a process of pondering such an extreme question. Every child would answer with a simple answer,

“No.”

“Okay why not?”

On it would go, especially when we had Jewish residents or both Jewish and Arabic children in our programs.

“Do you think it would be better to learn to listen to each other and try to understand their side and see if there was a way to find solutions rather than continue with condemning each other, blaming each other and making bullets. Again, “No,” was uniform.

“What would you do if you were in a position to influence each side or even one side?”

The sum effect of this method was transferring an abstract answer into real world solutions involving meetings, guns, compromises, farming together, and so forth. Andy added a thought-provoking statement. “The soldiers killing each other have families, even their own children and jobs. Wouldn’t they rather be at home? “On it went, and peace seemed like a good thing given the choice and an opportunity.

What we hoped would become their modus operandi was not rush to judgement in any situation or any idea or experience that would naturally occur in their personal lives and the world as a whole.

For Mohonk this was a particularly good time to influence children because they were adolescents. That is a period of time when the human brain goes through its last rather dramatic period of development particularly in the frontal lobes and especially the pre-frontal cortex.30 They are the principal areas of the human brain that deal with complex reasoning, critical thinking, planning, organizing and other so-called executive functions of a human as mentioned previously.

Going on with a half century of experience, we saw first-hand that children preferred to have hope that things would become better even if it seemed difficult. They answered questions. They were thinking. We discovered that children preferred that they had the chance to make changes in their lives and have a brighter future, that is, they preferred to believe in themselves rather than feel hopeless and lost. They were thinking and they valued their future. No matter the circumstances, no child preferred hate or anger to solving problems, no matter how angry or hateful they might have felt.at first. In our programs and residence, children preferred to get along. Their brain said so. Hope and getting along were rewarding. Over the years, we placed a small four-inch by two-inch attention-grabbing display in the center of a very large empty full-page display for major newspapers in our state:

NO SUCH THING AS A BAD KID

What child feeling there is hope;

and what child beginning to believe

in himself or herself would choose hate and anger.

GIVE OF YOURSELF THIS HOLIDAY SEASON

Such a statement was not offered as a pronouncement or assertion of what we believed was an insurmountable truth or how the brain learns best. It was offered as a question. It was offered to encourage those who read it to think, just as we did with the children we helped.

HOW THE BRAIN PAYS ATTENTION

The effect of incorporating our first two brain-based methods, How the Brain Learns Best, and How the Brain Thinks led to remarkable and unexpectedly moving stories of the children whose lives we had changed. We also realized that we still had left much of the brain out, and that set the stage for the inclusion of six additional brain-based methods.

One of those six was How the Brain Pays Attention.

Paying attention is a dynamic indispensable brain-based phenomenon. A human cannot function without the brain being able to block extraneous stimulation that is ever present and constantly bombards our senses and our memories. At this moment, the reader might want to stop and notice any sound that you hadn’t noticed while you were talking to your best friend. Every sense is blocked out by the attention centers of the brain until you are asked to notice them or necessity.31 Your brain enables you to pay attention to the words you are reading now. Many forms of attention deficit disorders (ADD) point to this disability. The areas of the brain that are involved in the process of paying attention include neural networks within the parietal, frontal, and temporal lobes. They all have direct or indirect connections with each other along with subcortical networks as seen in Figure 8.

Figure 8

Figure 8

Efforts to gain a child’s meaningful and undivided attention have been studied and guessed forever. Rewards, smiles, humor, threats or punishments and behavioral reinforcement methods incorporated the main stays. Most approaches had at least some success in grabbing a child’s attention in order to guide a child’s behavior and teach. However, there was no guiding star that fit every child in every situation. The results have varied as widely as the types of temperaments and personalities of children we wish to describe. However, neuroscience has given us direction in this labyrinth, and, at Mohonk, there was one mainstay that seemed to cross all boundaries.

Our first practical application was we did whatever it took to gain the attention of a child, without the use of threats or punishments.

Jake was ready to rip his mathematics textbook apart and toss it across the kitchen. “I hate this,” he yelled as he edged closer to total uncontrol. We could have restrained him or at least yelled or threatened Jake with consequences. We could have pleaded with him and bribed him with promises if he would only calm down and put his textbook down. We did neither. We wanted Jake to begin to think, but first we needed to get his attention and take it from there. Robert, one of our staff standing six feet from him, responded. “Great! I hate this too! Let’s go to school and paint the principal’s office black!” Jake paused abruptly. What an odd thing to say! “What!” he said in an expressive look of total confusion. Jake was now paying attention, and his anger was being subdued by cognitive control. His pre-frontal cortex was at least temporarily trying to make sense of what he just heard. That is how Jake’s brain was prompted to pay attention and begin to think of solutions.

Robert went on excitedly with a tone of support for Jake’s anger. “Would that work? Would that make the problem end? What would? Jake, what would work? You want to win, don’t you? Now Jake was contemplative. He was thinking, and not just reacting to fear, any threat, or reward. His undivided attention turned to thinking. That is what we wanted him to do. He was being empowered to think of a solution. After fifteen minutes of both serious and some buoyant humor, Jake came up with a good idea. He decided he would go to the student counselor’s office and ask for extra help with mathematics.

The next day we asked Jake about his emotional upheaval. We did not imply or suggest that he had done anything wrong. In fact, his anger was his motivation to solve his problem. Jake thanked us anyway, but we were much more enthusiastic. “Why did you bother to control yourself? Did we control you? Did you control yourself?” Jake was thinking again, and he recognized that he did the work, not us.

The success of such a momentary incident typified the interactions and atmosphere at Mohonk. Paying attention started the ball rolling and the rest followed, especially as it incorporated emotions.

HOW THE BRAIN FEELS

Learning and thinking always involve emotions in one way or another. The human brain has a complex anatomy and physiology related to emotions. It principally involves what is called the Limbic System. Please refer to Figure 9. The Limbic System itself is connected to virtually every other area and neural network of the human brain. This has been well studied, and emotions impact learning and thinking even if we do not see any outward expression of emotional behavior from the child. A child’s emotions may be under control, subdued, explosive and overwhelming or even unconscious. They can be hidden by monotonic expressionless thoughts and words. The Limbic System is simply the source for inhibiting or expressing every emotion that is part of human nature.

Ryan had been homeless for two weeks in frozen February, sometimes sleeping near a heat vent outside a factory. The police found him and woke him up. They learned he had run away after his family moved to another state and told him he could do whatever he wanted to. Apparently, there had been some deep dilemmas within his family.so Mohonk was the best stable refuge to lay his head for now.

When we opened the door, Ryan came in shivering, and his face looked frozen. He showed no emotion and did not even seem to care. He remained stoical and He was both cold and, even more, had no idea where he was and what was happening to his life. Finally, after Ryan was warm and after he devoured a plate full of lasagna and chocolate chip cookies at one-thirty in the morning, we asked him a series of unexpected, surprising questions with the intent of getting his undivided attention.

“Ryan, you seem like you are okay. Ryan looked up and was curious. He knew he was not okay and could not imagine he looked “okay.” That meant he was thinking “Would you rather go back outside and be left alone,” we then asked. Ryan did not want to do that. We knew that but wanted him to ponder the thought. He couldn’t say yes because he wanted to be inside where it was warm, surrounded by the smell of delicious food and surrounded by others who cared. By asking such direct, unexpected questions we had Ryan’s attention, and he was thinking about his life. Thinking about his life was now an easy step to take. Finally, his emotions and hurt poured out. Ryan looked to his side and cried without stopping. Ryan was letting out the emotions that laid deep inside him. His defenses were down. His emotions did not have to stop at the redlight. It was green to go. Five minutes later Ryan offered that he hoped he would be with his family again somehow. It only took one week for Ryan to recognize by himself that he was part of the solution, and he came up with ideas his parents would listen to without screams and threats from him or his parents. At least he would be willing to give it a try. The trying started when we contacted Ryan’s parents and were told he was at Mohonk. They were shocked worried to death and could not believe they left him to “take-care-of-yourself-and-grow-up”

For Ryan and his parents, it only took two weeks to come up with solutions that worked with everyone on board. On the third week Ryan returned to the home he loved. That also was his home until he was ready to challenge the unknown at college 16 months later.

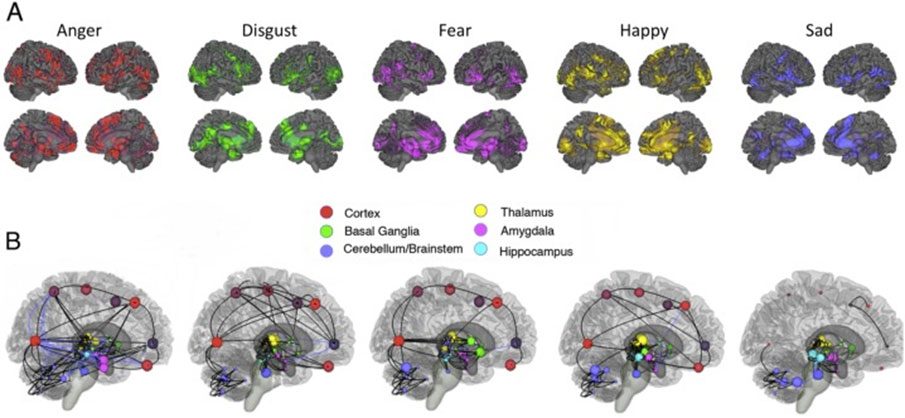

Neurocircuitry of basic emotions. Views of the representation of emotions in different subareas of the Limbic System The circles are networks, color-coded by anatomical system. Compared to other emotions, sadness includes dramatically reduced connectivity within the cortex, and between cortical and subcortical systems, while connectivity within cerebellar/brainstem systems seems rather exaggerated.

Neurocircuitry of basic emotions. Views of the representation of emotions in different subareas of the Limbic System The circles are networks, color-coded by anatomical system. Compared to other emotions, sadness includes dramatically reduced connectivity within the cortex, and between cortical and subcortical systems, while connectivity within cerebellar/brainstem systems seems rather exaggerated.

Figure 9

Emotions are always part of the equation of how children learn and deal with the ups and downs of life. Emotions cannot be dismissed as insignificant only because we do not witness any emotional responses. The child and his brain only inhibit their expression to those around him or even to the child himself. Inhibition is not dismissal of emotion. Rather it is only in hibernation. Underlying pain, confusion, are still there and have not solved any problem at its core. We never wanted to suppress or hide from any emotion no matter what the nature of the emotion was whether expressed or inhibited. When expressed, defenses are much more likely to decrease. The result is insight and opportunity awaken both for the child and those who are in his care. This is based upon the way the child’s brain worked, and it deserved a name. We called it How the Brain Feels.

The primary practical application we used was to stimulate and reinforce the expression of all emotional behavior, especially outbursts of anger, floods of tears, or emotions that were repressed but were stirring inside, as was in Ryan’s head. Most important was that every child knew that they were not judged by any emotional expression of their humanity. This was also important because at first children often judge themselves based upon the emotional expressions that leak out. “I get mad at everybody. It’s just the way I am.” “I am just depressed all the time. I can’t change.” Not true. We see such exclamations as providing opportunities for growth.

Peter just accepted that he was a bad kid because he blew up so easily, and trouble was his middle name. Peter had been suspended from school before his parents asked us to try and “straighten him out.” Regular therapy had done little except to convince him that he was a bad kid. We asked Peter about that. “Peter, do you like being a bad kid.” He answered that with an exclamatory offensive tone. “Why would you even think that?” and he began to get up out of his chair to leave. “Excellent,” was our response. “Peter, you just showed us that you’re not a bad kid and don’t want to be a bad kid and don’t want to blow up. How do you think you could do that? Peter’s attention was fastened on his face, and now he was thinking. One could tell by his silence and his eyes. His anger left him, and he began to share his life with us. Peter revealed how we was suspended twice for threatening bullies who were picking on weaker students at his school, the same as he had done when he stood between his father and his younger brother. His father beat them both. Peter was a good kid. He used his strong character to do good things, but no one saw that. Peter came to realize he was, at heart, a good kid, not a bad kid. His father and mother separated. His father had work to do on himself. While separated he attended family sessions at Mohonk that dealt with parents with such difficulties and Peter also had work to do on himself. Then, after three months, the family gave it a try together. Peter returned home for one weekend at a time. So did his father. Finally, despite the scars, there was no more crippling turbulence, no more beatings. As important as that was, Peter discovered that he was a brave kid who had the courage to try and right wrong. Peter’s days in the gutter were gone.

HOW THE BRAIN INTERPRETS SENSORY INFORMATION AND HOW TH BRAIN RESPONDS TO SENSORY INFORMATION

As our brain-based methods showed, we were improving the lives of children and families, two additional rather technical and cold-sounding brain-based methods could be identified. They reflect a continuous steam where one has a direct correspondence to the other. Every sensory input to a child’s brain results in a response even if we cannot visually or aurally detect it. These two also brought the attention to the value and importance of bringing neuroscience to the forefront to discover more effective ways to raise, educate and help children in need. They are represented in separate neural networks of the human brain, and impact learning, emotions and all behavior in distinct ways (Figure 10, 11).

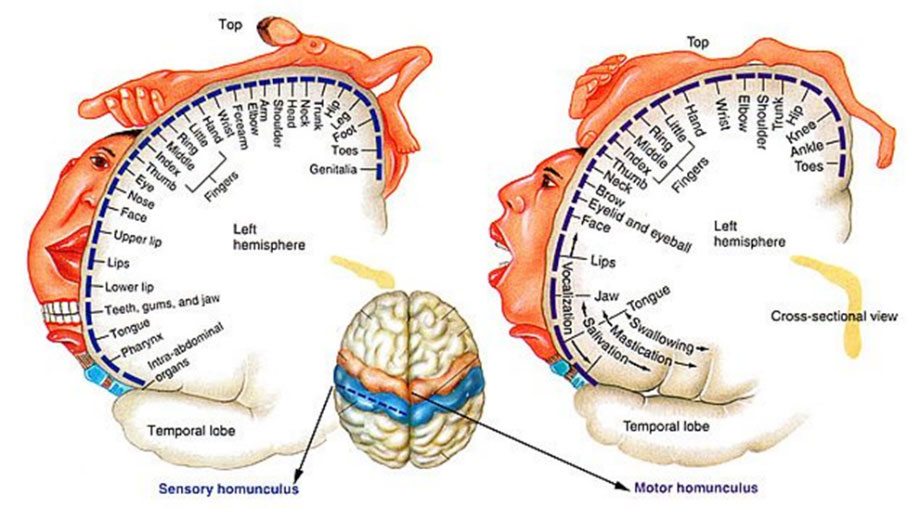

A child’s motor response to sensory stimulation is the other side of the same mountain. Responses mean the movement of muscles and include speech and writing as much as jumping over a four-meter crossbar in pole vaulting or breaking for a red light. Each assembly of muscular responses is represented by different areas of the cerebral cortex that includes the primary motor cortex interconnected with other motor areas of the human brain.

Every child has these same sensory and motor areas of their brains. Still every child is unique based upon genetic predispositions and environmental influences. Maria Montessori would nod her head in approval. Montessori methods encourage independent exploration that incorporates learning through multi-sensory experiences and the concomitant way children respond.32 Harold Gardner would concur. His theory of “multiple intelligences” emphasizes that all children have a distinct collection of at least seven types of intelligences spanning linguistic to spatial and bodily-kinesthetic abilities.33 That reflects the fact that children have different levels of ability in any class of aptitude or behavior we wish to define. linguistic understanding while others may have predominant and divergent abilities in such areas as spatial orientation, muscular dexterity, artistic expression in dance and painting among other gifts. The common bond of all requires sensory exposure to very different types of environmental stimulation and the impact they have on the way a child responds, especially within the first three to five years of life and then again between the eleventh and sixteenth years of life. The brain concurs. He lives with himself. At Mohonk there were two brain-based methods that incorporated these indispensable necessities for child development. We called them How the Brain Interprets Sensory Information and How the Brain Responds to Sensory Stimulation

l

l

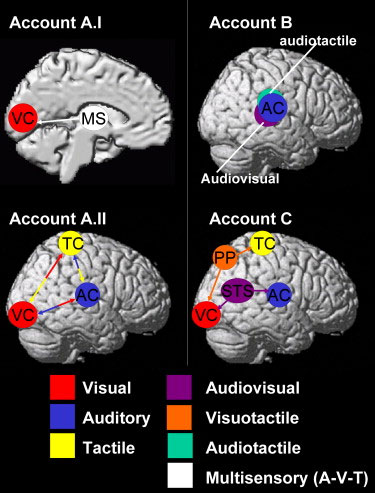

In the human brain each human sense is centered in different neural networks and even though they are all interconnected, humans have different levels of ability based upon genetic predispositions and sensory influences.

Figure 10

The motor and sensory regions of the human brain reflect the relative importance that different areas of the sensory and motor systems play in the life of a human.

Figure 11

In order to practice these two brain-based methods with children we developed one particularly embracing practical application. We exposed every child to as many sensory experiences as possible and have them learn from the responses they made. In turn, all of our brain-based methods came into play. Children paid attention, had an abundance of emotional feelings, and learned and began to think about the consequences of how they responded and what they might do again.

In society, lawyers do not just read about legal practices, they practice them their peers or professors. Doctors are required to have an internship and residency before they become licensed practitioners. Starting at sixteen years of age, adolescents are required to practice driving before they can get a license to drive, and pilots as young as sixteen are also required to practice flying before they can fly solo. All of these practices have a common brain base. They all involve learning how to respond to what their senses take-in regardless of how well they do on written examinations. At Mohonk, we wanted their experiences to be their internship for their own personal lives. .

We often had meaningful conversations with our adventurous youth on taking chances. Most adolescents believed they could drive very well after passing their written driving test examination and having few or even any driving lessons. We then asked a simple question because that is how the brain begins to think.

“Which of these two pilots would you trust to fly you over the tallest waterfall in the world, Angel Falls in Venezuela, 2,212 feet high.”

We then showed them photographs and gave them a choice.

“They are identical twins and have identical four-seater single propeller airplanes .Twin 1 had aced his written pilot’s examination with a perfect score and did vey well on his three test lights. Twin 2 had never taken a class on flying and never even took the written examination, but he as able to get the chance to fly and take control of an airplane. That began his career and after eighteen years of flying through fog, and hailstones, blinding clouds and propellers that stall out with no accidents at all, here’s a question. Who would you choose to take you on a flight over the jungle and over Angel Falls?”

The voting was unanimous- Twin 2, except for Stewart “I wouldn’t take either. I’m scared to death of heights!” The point was clear. Sensory experience and responding to what you experience has a benefit words alone cannot replicate, only contribute to.

Calvin wanted to learn to fly but was nervous about crashing our glider.